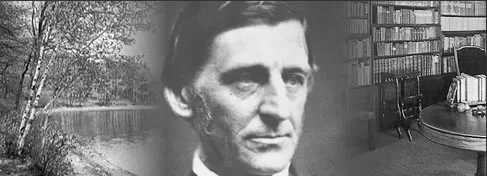

On June 16th The Ralph Waldo Emerson Institute gathered at the Concord Museum in Concord Massachusetts for a showing of "Emerson: the Ideal in America", a biography of Ralph Waldo Emerson. We were joined by two Emerson scholars; Professor Sarah Wider from Colgate College, and Richard Grossman, author of "A Year with Emerson" in discussion after the viewing. Also present were David Beardsley who wrote and directed the video, and Jim Manley moderated.

Below is a synopsis of audience questions and group discussion that followed. Responses to questions were collectively answered by Sarah Wider, Richard Grossman, David Beardsley and Jim Manley.

Q: How did you choose the music? There was a particular track that sounded like a Gregorian chant, was that American music?

A: Yes, the sound track is entirely American music of the period. The piece that you are referring to is the "Narraganset Hymn" which was composed by an American composer influenced by the classical Gregorian music.

Q: What would Emerson be doing if he were here today? What role might he play in society?

A: Interesting question, difficult to answer…but he would probably be a man of the media since he was consistently drawn to the ‘new' in his time…it was suggested later on in the evening that perhaps Emerson may have been a Bill Moyers like personage-in light of the work Moyers has done with Joseph Campbell and many programs examining the role of spiritual life in modern culture. As an educator, he might be supportive of what is generally known as the "Socratic method" of teaching and interaction with students-where students are encouraged to reflect on the world around them, problems, or texts, and taught to utilize and trust in their own analysis of intellectual and spiritual issues. [In response the panelists also talked a great deal about individualized interaction with students, listening closely to their ideas, so that each individual can develop his/her own ideas]. In pedagogical terms, this is also known as "constructivist learning". He would probably be a fan of what we call informal education; ‘adult education', or continuing education as life long learners. Some of you have mentioned that the state of education today seems ‘dumbed down'; in the age of Google kids are now free to learn what they want, rather than what they might benefit from. Emerson would certainly have something to say about the persistent inequalities in our educational system.

Q: How do you reconcile the fact that Emerson was a voracious reader of all kinds of texts; religious, philosophical, scientific, historical and pedagogical-with his admonition "never imitate"? Isn't this a contradiction?

A: Emerson was a keen intellect and a terrific synthesizer of ideas; its true he read widely, but in his analysis of other texts he was looking for the similarities among all the world's major religious traditions and their moral and ethical core, or, .belief in the continuity of thought across cultural differences, suggesting the presence of a larger universal spirit from which all differences arise-this is not imitation, but more meta-analysis. These readings (i.e., the Bhagavad-Gita,Upanishads, Goethe, Hafiz) seem to affirm Emerson's belief in the uniqueness of the existence of each individual human being. So, rather than imitation, his study of other religions made him a champion of man's divine spark and the ‘genius within'-a genius that always extended far beyond the limited personal self. As Emerson says in "Friendship" " I ought to be equal to every relation, suggesting how each indivicual must become larger in order to stand in good relation with the world.

Q: At the time in which he lived, what was the public reaction to Emerson's comments about the staleness and triviality of the religious establishment? Was he perceived as a revolutionary?

A: As a minister of the Second Church in Boston, Emerson was in constant conversation with his congregation about the controversial religious ideas of the day (for example: how to interpret "miracles," how to interpret the special character or nature of Jesus). His congregation affirmed and indeed joined his style of questioning and probing established order, but in 1832, they chose not to relinquish the established form of communion, a practice Emerson felt Jesus had not intended to be practiced as a ritual. This disagreement gave him a convenient opportunity to leave an institution that was an increasingly difficult fit for him. He was becoming increasingly controversial as his famous Divinity School Address at Harvard in 1838 would show, and as his published writings would continue to demonstrate. Reviewers of the first two volumes of essays in the 1840s warned that such books should be kept out of the hands of youth.

To put Emerson's celebrity status in context, generally speaking, traveling lecturers were the ‘rock stars' of social life and commanded the following of the press. Emerson was very much a public figure. For example, Emerson's letter President Van Buren protesting the Indian Removal Acts was a bold move. The letter was not simply a private matter of a concerned citizen but written as a public document, sent and printed in the Boston papers. He was a notable friend of Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts who was the political leader of antislavery forces; Emerson was very critical of Daniel Webster's political career as a Senator. So, he was very much a public person of his time.

Q: As a student new to Emerson, how do begin to understand him? His language is so rich (some might say dense)?

A: Read Emerson aloud. Read Emerson with others. The Ralph Waldo Emerson Institute is giving a lot of thought to how they can support and encourage reading circles about Emerson through the web site (RWE.org). The language Emerson uses is multifaceted; but it is also meant to entertain; there is humor in his writings, there is crisp imagery, and it can be a treat for the ear as well. Above all, Emerson loved conversation-he lived for conversation with friends and colleagues. Emerson's essays invite conversation-do not mistake them as sermons or diatribes!