To see this story with its related links on the Guardian Unlimited Books site, go to http://books.guardian.co.uk

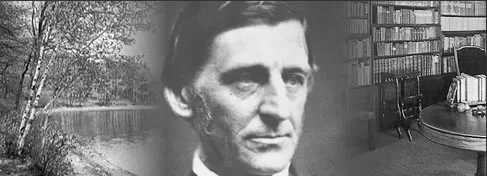

The Sage of Concord

Philosopher, poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson helped define US identity in the 19th century. Today, 200 years after his birth, his views on power, rejection of Old Europe and belief in a personal god are even more influential, pervading American culture and politics, argues Harold Bloom

Saturday May 24 2003

The Guardian

Born on May 25, 1803, Emerson is closer to us than ever on his 200th birthday. In America, we continue to have Emersonians of the left (the post-pragmatist Richard Rorty) and of the right (a swarm of libertarian Republicans, who exalt President Bush the second). The Emersonian vision of self-reliance inspired both the humane philosopher, John Dewey, and the first Henry Ford (circulator of  The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion ). Emerson remains the central figure in American culture and informs our politics, as well as our unofficial religion, which I regard as more Emersonian than Christian, despite nearly all received opinion on this matter.

Born on May 25, 1803, Emerson is closer to us than ever on his 200th birthday. In America, we continue to have Emersonians of the left (the post-pragmatist Richard Rorty) and of the right (a swarm of libertarian Republicans, who exalt President Bush the second). The Emersonian vision of self-reliance inspired both the humane philosopher, John Dewey, and the first Henry Ford (circulator of  The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion ). Emerson remains the central figure in American culture and informs our politics, as well as our unofficial religion, which I regard as more Emersonian than Christian, despite nearly all received opinion on this matter.

In the domain of American literature, Emerson was eclipsed during the era of TS Eliot, but was revived in the mid-1960s and is again what he was in his own time, and directly after, the dominant sage of the American imagination. I recall sadly the American academic and literary scene of the 1950s, when Emerson was under the ban of Eliot, who had proclaimed: “The essays of Emerson are already an encumbrance.” I enjoy the thought of Eliot reading my favourite sentence in the essay, “Self-Reliance”: “As men’s prayers are a disease of the will, so are their creeds a disease of the intellect.” Â

It delights me that, in 2003, there is an abundance in Emerson to go on offending, as well as inspiring, multitudes. “O you man without a handle!” was the exasperated outcry of his disciple, Henry James Sr, father of William the philosopher-psychologist and Henry the novelist. Like Hamlet, Emerson has no handle, and no ideology. And like another disciple, the greatest American poet, Walt Whitman, Emerson was not bothered by self-contradiction, since he knew he contained endless multitudes: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Â

Almost all post-Emersonian writers of real eminence in American literature are either passionately devoted to him or moved to negate him, rather ambiguously in the stances of Hawthorne and Melville, but fiercely in the case of Poe and most southerners after him. (Emerson shrugged off Poe as “the jingle man”.) At every lunch that I happily shared with the poet-novelist Robert Penn Warren, he would denounce Emerson as the devil. Warren was anything but dogmatic, whether on literary or spiritual matters, but he blamed Emerson for the murderous John Brown – whose violent crusade against slavery sparked the Civil war – and for most of what was destructive in American culture. C Vann Woodward, a historian of extraordinary distinction, told me many times that Emerson could not be forgiven for the essay “History”, which never ceases to give me joy with its sentence: “There is no history, only biography.” On the other side, there is the testimony of Whitman, celebrating Emerson as the explorer who led us all to “the shores of America”. Thoreau and Emily Dickinson can be said to evade Emerson, but only after absorbing him, while Robert Frost was the most exuberant of all affirmers of Emerson. There are too many to cite: no single sage in English literature, not Dr Johnson nor Coleridge, is as inescapable as Emerson goes on being for American poets and storytellers. Â

Emerson at his best was an authentic poet, but it his prose – essays, journals, lectures – that is his triumph, both as eloquence and as insight. After Shakespeare, it matches anything else in the language: Swift, Johnson, Burke, Hazlitt. As an essayist, Emerson professedly follows Montaigne, and Montaigne’s precursors: Plato, Plutarch, Seneca. Montaigne and Shakespeare were, for Emerson, the two writers always with him. Â

Why did Emerson have so unique an influence upon his contemporaries and those who wrote later? Originally a Unitarian minister, Emerson abandoned his post because he knew only the god within, which he defined as the best and oldest part of his self. He became a wisdom writer, practising what could be called interior oratory, but also a public lecturer. Many of his essays began as journal entries, were transformed into lectures, and then were refined for publication. Â

As a lecturer, and as a writer, Emerson manifested a remarkable conversionary power, very different in kind from evangelical salvations. The leap in awareness Emerson offered is not radically new, and is related to the effect Shakespeare has on us, allowing us to see what already is there yet which would not be available except for Shakespeare’s mediation. I am suggesting Emerson is not an Idealist nor Transcend-ental philosopher, but an experiential essayist, like Montaigne, and so more a dramatist of the self than a mystic: Â

“That is always best which gives me to myself. The sublime is excited in me by the great stoical doctrine, obey thyself. That which shows God out of me, makes me a wart and a wen. There is no longer a necessary reason for my being.” Â

Emerson suggests we give ourselves to ourselves; that each of us can be cosmos rather than chaos. Autonomy ought to be our aim, though Emerson intends a healing of the self, rather than alienation from society. Even such a self-mending reveres transition, rather than any final state of the individual. One of the central passages is from the essay, “Self-Reliance”: “Life only avails, not the having lived. Power ceases in the instant of repose; it resides in the moment of transition from a past to a new state, in the shooting of a gulf, in the darting to an aim. This one fact turns all riches to poverty, all reputation to shame, confounds the saint with the rogue, shoves Jesus and Judas equally aside. Why, then, do we prate of self-reliance? Inasmuch as the soul is present, there will be power not confident but agent. To talk of reliance is a poor external way of speaking. Speak rather of that which relies, because it works and is.” Â

Nothing is more American, whether catastrophic or amiable, than that Emersonian formula concerning power: “it resides in the moment of transition from a past to a new state, in the shooting of a gulf, in the darting to an aim”. Throughout his own lifetime, Emerson was ambiguously on the left, but then the crusade against slavery, and the south, over-determined his political choices. Much as I love Emerson, it is important to remember always that he valued power for its own sake. If he is a moral essayist, the morality involved is not primarily either humane or humanistic. Â

As I grow older, I find Emerson to be strongest in  The Conduct of Life, published in December 1860, four months after the south began the Civil war by firing upon Fort Sumter. Something vital in Emerson began slowly to burn out in the emotional stress of the war, perhaps because his hatred of the south intensified – he said that John Brown’s execution had made the gallows as “glorious as the cross”.  Society and Solitude (1870) manifests a falling-off, even more apparent in  Letters and Social Aims (1875). His last five years, from 1877 on, saw an end to his memory and his cognitive abilities. But in  The Conduct of Life , written in his mid-50s, he establishes a crucial last work for Americans, in particular through a grand triad of essays: “Fate”, “Power”, “Illusions”. “Power” is the centre, and might have been composed last week, in its shrewd sense of Americans, so little changed a century-and-a-half later: “The rough and ready style which belongs to a people of sailors, foresters, farmers, and mechanics, has its advantages. Power educates the potentate. As long as our people quote English standards they dwarf their own proportions. The very word ‘commerce’ has only an English meaning, and is  pinched to the cramp exigencies of English experience. The commerce of rivers, the commerce of railroads, and who knows but the commerce of air-balloons, must add an American extension to the pond-hole of admiralty. As long as our people quote English standards, they will miss the sovereignty of power; but let these rough riders – legislators in shirt-sleeves – Hoosier, Sucker, Wolverine, Badger – or whatever hard head Arkansas, Oregon, or Utah sends, half orator, half assassin, to represent its wrath and cupidity at Washington – let these drive as they may; and the disposition of territories and public lands, the necessity of balancing and keeping at bay the snarling majorities of German, Irish, and of native millions, will bestow promptness, address, and reason, at last, on our buffalo-hunter, and authority and majesty of manners. The instinct of the people is right. Men expect from good whigs, put into office by the respectability of the country, much less skill to deal with Mexico, Spain, Britain, or with our own malcontent members, than from some strong transgressor, like Jefferson, or Jackson, who first conquers his own government, and then uses the same genius to conquer the foreigner. ” Â

I have quoted this long paragraph partly for its perpetual relevance, and partly for its Emersonian self-revelation, and exuberant amoralism. This cultural nationalism, invariably directed against the English, has no illusions as to what Emerson will go on to call (quite cheerfully) “the power of lynch law, of soldiers and pirates”, of bullies of every variety. These roughs represent the power of violence, only a slightly lower order, for Emerson, of the violence of power: “Those who have most of this coarse energy – the ‘bruisers’, who have run the gauntlet of caucus and tavern through the county or the state, have their own vices, but they have the good nature of strength and courage. Fierce and unscrupulous, they are usually frank and direct, and above falsehood. Our politics fall into bad hands, and churchmen and men of refinement, it seems agreed, are not fit persons to send to Congress. Politics is a deleterious profession, like some poisonous handicrafts. Men in power have no opinions, but may be had cheap for any opinion, for any purpose – and if it be only a question between the most civil and the most forcible, I lean to the last. These Hoosiers and Suckers are really better than the snivelling opposition. Their wrath is at least of a bold and manly cast. They see, against the unanimous declarations of the people, how much crime the people will bear; they proceed from step to step, and they have calculated but too justly upon their Excellencies, the New England governors, and upon their Honours, the New England legislators. The messages of the governors and the resolutions of the legislatures are a proverb for expressing a sham virtuous indignation, which, in the course of events, is sure to be belied.” Â

Fundamentally, America in 1860 and in 2003 are little different. Our current bruisers (Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld et al) are distinctly not “frank and direct, and above falsehood”, because they come from the corporate world, but certainly they know “how much crime the people will bear”, and much of the opposition we can muster is, alas “snivelling”. An uncanny ironist, as a prophet must be, Emerson is archetypically American in his appreciation of power: “In history, the great moment is, when the savage is just ceasing to be a savage, with all his hairy Pelasgic strength directed on his opening sense of beauty – and you have Pericles and Phidias – not yet passed over into the Corinthian civility. Everything good in nature and the world is in that moment of transition, when the swarthy juices still flow plentifully from nature, but their astringency or acridity is got out by ethics and humanity.” Â

The “moment of transition” again is emphasised: power is always at the crossing. Americans can read Emerson without reading him: that includes everyone in Washington DC pressing for power in the Persian Gulf. I return to the paradox of Emerson’s influence: Peace Marchers and Bushians alike are Emerson’s heirs in his dialectics of power. Â

I am much happier thinking about Emerson’s effect upon Whitman and Frost, Wallace Stevens and Hart Crane, than upon American geopolitics, but I fear the two arenas are difficult to sever. What matters most about Emerson is that he is the theologian of the American religion of self-reliance, which comes at a high cost of confirmation. Every two years Gallup conducts a poll on religion. The somewhat disconcerting central facts do not change: 93% of Americans say they believe in God, and 89% affirm that God loves her or him on a personal and individual basis. In no other country (that I know of) have almost nine out of ten so intimate a relationship with God. Â

I am persuaded that Emerson, a master ironist, would be uneasy at such progeny, but his knowledge of the god within certainly contributed to this aspect of the American religion. Among his early poems, abandoned by him in manuscript, there are startling intimations of the American wildness in religion, a  fusion of Enthusiasm and a native Gnosticism: Â

I will not live out of me

I will not see with others’ eyes Â

My good is good, my evil ill  Â

I would be free – I cannot be Â

While I take things as others please to rate them Â

I dare attempt to lay out my own road

That which myself delights in shall be Good

That which I do not want -indifferent,

That which I hate is Bad. That’s flat Â

Henceforth, please God, forever I forego

The yoke of men’s opinions. I will be

Lighthearted as a bird & live with God.

I find him in the bottom of my heart Â

I hear continually his Voice therein

And books, & priests, & worlds, I less esteem

Who says the heart’s a blind guide? It is not.

My heart did never counsel me to sin

I wonder where it got its wisdom Â

For in the darkest maze amid the sweetest baits

Or amid horrid dangers never once Â

Did that gentle Angel fail of his oracle Â

The little needle always knows the northÂ

The little bird remembereth his note

And this wise Seer never errs Â

I never taught it what it teaches me

I only follow when I act aright.

Whence then did this Omniscient Spirit come?

>From God it came. It is the Deity. Â

This fragment has the authentic accent of the American religion. As the voice of Emerson, it fascinates me, but causes anxiety when I imagine it being uttered by my Pentecostal, Southern Baptist and Mormon contemporaries. In forming the mind of America, he prophesised a crazy salad to go with our meat. He spoke of himself as an endless experimenter, with no past at his back. Old Europe was rejected by him, in favour of the American Adam. Semi-literate as the Bush bunch are, their vision of the Evening Land imposing ideas of order upon the universe has an implied link to Emersonianism. Â

But the sage of Concord was also the benign father of the Americanism of American literature – only a southern author would quarrel with this statement. No other critic has stressed so productively the use of literature for life. There are hundreds of Emersonian aphorisms that reverberate for me, but none more than this, embedded in the first paragraph of “Self Reliance”: “In every work of genius we recognise our own rejected thoughts: they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.” Â

Several of our best living writers have quoted that to me, and I have been quoting it to my students these last four decades. “I read for the lustres,” Emerson remarked, and filled his notebooks with them, drawing particularly upon Plutarch’s  Moralia and Montaigne’s  Essays . Doubtless, there are many other ways to read, but I like best Emerson’s way, which is to take back what is your own, wherever you may find it. Â

“All power is of one kind, a sharing of the nature of the world”: that is another of Emerson’s sayings, and is subject to dark interpretations in a US determined to share in the nature of all the world. But Emerson, however he may be employed now, loathed the American imperialism of the Mexican war, and would be sublimely ironic at our conquest of Baghdad. Â

Emerson looked frail, but he was a survivor. The family malady was tuberculosis, and Emerson had to endure the loss of his first wife, Ellen; of his brothers Edward and Charles; and of his young son, Waldo (to scarlet fever). These were all he had loved best, but a strong stoicism prevailed in him. For all his ailments, Emerson’s travels and exertions as a lecturer rival Charles Dickens’ theatrical readings, and those killed Dickens. A passion for teaching self-trust drove Emerson through an astonishing public career, in which he became a kind of northern institution of one, rather than the icon of Transcendentalism. Though his books sold well, Emerson’s fame and influence came as a popular lecturer, a kind of displacement of his earlier role as an exemplary Unitarian minister. Â

Emerson cheerfully would deliver a series, often of 10 or 12 orations, for good fees, in city after city, and on very diverse topics: the philosophy of history, human life, human culture, representative men (which became a book), mind and manners, anti-slavery, American civilisation or whatever he willed. Sometimes he would deliver 70-80 lectures in a year, in locales spread widely throughout Canada and the United States (always excluding the south). Wherever he went, Emerson encountered sold-out houses of enthusiastic auditors. Contemporaries who attended testify to the sage’s charismatic presence: serene, restrained, yet invariably intense, and spiritually formidable. Â

Emerson seems most himself in his marvellous journals, begun on January 25, 1820, under the auspicious title: “The Wide World”. He was 16, and already himself, and continued the journals faithfully until 1875, when they start to trail off, as his mind wanders away from him. Â

An extraordinary work of self-creation, Emerson’s 55 years of journals are his authentic greatness, insofar as his writing could convey the apparent miracle of his voice. Huge as the journals are, they need to be read complete, because Emerson’s mind has become the mind of America. I am aware that this is not always a good thing, now that a self-reliant US bids to become a 21-century version of the Roman empire. In fairness again to the prophetic Emerson, he vehemently opposed the admission of Texas to the Union, and wrote and lectured against the Mexican war, the archetype of America’s Iraqi wars, and doubtless of wars to come. Â

In his own century, Emerson’s power of contamination was unique, and even writers who backed away from him could not fail to absorb his stance. Herman Melville attended all Emerson’s lectures in New York City, and uneasily read the essays. He satirises the sage in  Pierre and in  The Confidence-Man , but both Ahab and Ishmael in  Moby-Dick are Emersonians. Haw-thorne, a walking companion who silently resisted the prophet of self-reliance, nevertheless makes Hester Prynne, heroine of  The Scarlet Letter, an Emersonian before Emerson. Henry James, who tried to condescend to his father’s friend and master, goes beyond Hester Prynne in the overtly Emersonian Isabel Archer of  The Portrait of a Lady. No one, after Emerson, has taken up the burden of the literary representation of Americanness or Americans without returning to Emerson, frequently without knowing it. Â

“A man is a god in ruins” and “man is the dwarf of himself”: these Emersonian formulations are Hamlet-like in spirit, and can be as self-destructive as Hamlet was. Yet I thrill to Emerson’s extravagant summonings to a greatness we do not yet know or understand. He had married twice: tragically but with deep love in the first instance with the doomed Ellen; happily enough but with no fierce passion towards the formidable Lidian. In the unsettling “Illusions” of  The Conduct of Life, marriage is not exactly idealised: “We are not very much to blame for our bad marriages. We live amid hallucinations; and this especial trap is laid to trip up our feet with, and all are tripped up first or last.” Â

“Hallucinations” seems a strong word there, but Emerson genially assures us that most of what we live out is illusion: Â

“We cannot write the order of the variable winds. How can we penetrate the law of our shifting moods and susceptibility? Yet they differ as all and nothing. Instead of the firmament of yesterday, which our eyes require, it is today an eggshell which coops us in; we cannot even see what or where our stars of destiny are. From day to day, the capital facts of human life are hidden from our eyes. Suddenly the mist rolls up, and reveals them, and we think how much good time is gone, that might have  been saved, had any hint of these things been shown. A sudden rise in the road shows us the system of mountains, and all the summits, which have been just as near us all the year, but quite out of mind. But these alternations are not without their order, and we are parties to our various fortune. If life seem a succession of dreams, yet poetic justice is done in dreams also. The visions of good men are good; it is the undisciplined will that is whipped with bad thoughts and bad fortunes. When we break the laws, we lose our hold on the central reality. Like sick men in hospitals, we change only from bed to bed, from one folly to another; and it cannot signify much what becomes of such castaways – wailing, stupid, comatose creatures – lifted from bed to bed, from the nothing of life to the nothing of death.” Â

The grim charm of Emerson, and his wisdom, are caught imperishably in that characteristic paragraph from the essay, “Illusions”. How difficult it is to explicate this subtle prose-poetry: is Emerson exalting whim (as he does elsewhere) while warning us that “the laws” are not to be evaded? His reader needs to bring nearly all of him to the consideration of each fresh enigma: “The intellect is stimulated by the statement of truth in a trope, and the will by clothing the laws of life in illusions.” Â

Emerson will not tell us so, but we need to juxtapose this sentence from “Illusions” with the aphorism I quoted earlier from “Self-Reliance”: “As men’s prayers are a disease of the will, so are their creeds a disease of the intellect.” Â

Prayer then is illusory and creeds are less healthy than tropes or metaphors for “the statement of truth”. To sum up Emerson is all but impossible: he affirms shocking antitheses. And yet I want to conclude this birthday salute by finding his best balance in that grand death-march of an essay, “Fate”, in  The Conduct of Life : “Nor can he blink the free will. To hazard the contradiction – freedom is necessary. If you please to plant yourself on the side of Fate, and say, Fate is all; then we say, a part of Fate is the freedom of man. Forever wells up the impulse of choosing and acting in the soul. Intellect annuls Fate. So far as a man thinks, he is free.” Â

I hear, in the foreground of this, the stance of Hamlet, at once the freest of Shakespeare’s “free artists of themselves” [Hegel], but also the most fated. Emerson is his own Hamlet, and argues for what he famously calls “the double consciousness”, credited by WEB DuBois, crucial African-American thinker, as being one of his starting-points: “A man must ride alternately on the horses of his private and his public nature, as the equestrians in the circus throw themselves nimbly from horse to horse, or plant one foot on the back of one, and the other foot on the back of the other. So when a man is the victim of his fate, has sciatica in his loins, and cramp in his mind; a club-foot and a club in his wit; a sour face, and a selfish temper; a strut in his gait, and a conceit in his affectation; or is ground to powder by the vice of his race; he is to rally on his relation to the Universe, which his ruin benefits. Leaving the dæmon who suffers, he is to take sides with the Deity who secures universal benefit by his pain.” Â

Though I am grimly impressed by this final Emerson, who engendered the poets Edwin Arlington Robinson and Frost, I am not likely to rally in my relation to the universe, which my ruin benefits. That is too much like the very American maxim: “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.” The wording of that pragmatic maxim is not Emersonian, but the sentiment is.

© Harold Bloom 2003

Copyright Guardian Newspapers Limited